Ever wonder how business is like country music? Well, in both cases, Cash is King. This course will show you how to read and analyze a cash flow statement…not country music.

What’s a Cash Flow Statement?

In country music, Johnny Cash is the undisputed master of songs about hurtin’ and healin’ and pullin’ on through. In business, cash is the undisputed master of the same thing (sort of). A company can be in great shape on its balance sheet and doing fine on its revenues. But if its cash flow is hurting, it will have to do a lot of healing in order to pull on through. Cash can really make or break a company.

The Cash Flow Statement Tells It Like It Is

A cash flow statement records how much money flowed into the company over a given period and how much money flowed out. Inflows can be from anything—usually a company’s regular sales provide the biggest source, but it can also bring money in from things like selling assets it owns.

Outflows come from a variety of things—paying for raw materials, meeting payroll expenses, and just about anything it takes to keep the company operating so that the lights don’t go out.

Cash flow for a company is like oxygen for a person. The body may be in great shape, but if for some reason a person is having trouble breathing, organs can get damaged and the whole body can die. Similarly in a company, if cash isn’t circulating around a company the way it is supposed to—with money coming in from customers and money going out to payroll, suppliers and lenders—the company can experience serious damage and even fold.

Too Much Success? Impossible is Nothing.

Cash flow can tell you things that the Balance Sheet and Income Statement can’t. Here’s an example:

Imagine a yogurt company that lands a contract to supply its tasty frozen yogurt to McDonald’s. Obviously winning that account is a huge success: after all, the company now has a reliable, wealthy customer that promises to buy large volumes every quarter. It looks like the future is guaranteed!

Not so fast. Maybe the company has bitten off more than it can chew. Suddenly it’s no longer a small operation:

- it has to buy more cows;

- equipment;

- storage room;

- more trucks;

- …more of everything.

And McDonald’s will only pay for what it receives from the company every month. That means that at the beginning of the contract, the company has to put out a lot more money in capital costs than it will bring in from sales.

So if the company can’t find investors or borrow money from the bank, it won’t be able to meet its commitment to supply McDonald’s—who will quickly look elsewhere for their massive supply of frozen yogurt. Even with a juicy contract from a giant like McDonald’s, the company can’t make a go of things. Because of a cash flow problem, it’s facing collapse.

Cash Flow From Operations

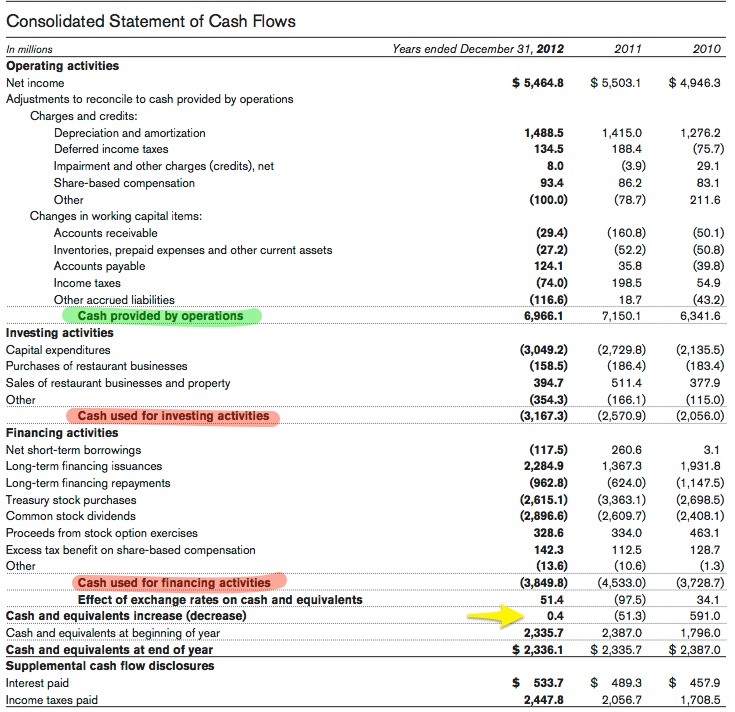

Time to take a look at the Cash Flow Statement for a real company: McDonald’s. You’ll see that it shows cash flow from three big categories: Operating activities; Investing activities; and Financing activities.

For a lot of investors, cash flow from operating activities is the most important of these three. They feel it’s the best measure of a company’s ability to keep afloat over the long term. The reason is pretty simple: if a company doesn’t have a positive cash flow from its day-to-day operations, it has to borrow money to keep going.

And that raises a question: how long is this going to go on for? Having to borrow to get through a short period is not a problem; having to borrow constantly means that maybe the company shouldn’t really be in business at all…

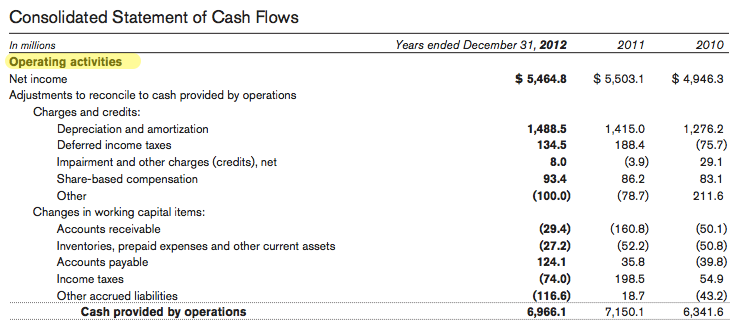

In McDonald’s case, operating activities contribute a big chunk of cash. Net income (which we saw in the course on the Income Statement) in 2012 was $5.5 billion, and that was the bulk of the net cash flowing into the company. But there were also other items, and these are divided into two categories: Charges and credits and Changes in working capital.

Charges and credits

These are items that relate to rules about accounting. The most important ones are listed below:

- Depreciation and amortization: This is an accounting term that refers to the decline in the value of certain fixed assets (things like wear and tear on equipment). Companies are allowed by accounting rules to write off a portion of that decline for tax purposes every year. Doing so increases their net income, so this is recorded as positive to cash flow (even though no cash ever changes hands with depreciation). In 2012, it contributed $1.5 billion to McDonald’s cash position.

- Deferred income taxes: No, this is not McDonald’s telling the tax man it would rather pay its taxes next year. It’s another accounting term that relates to the taxes McDonald’s pays on depreciating assets. (Look, it’s only $135 million, so fuggedaboutit.)

- Share-based compensation: This is money that McDonald’s paid to employees in the form of shares or the option to buy shares. In 2012, this amounted to $93 million—and by paying this amount in kind instead of in cash, it added to cash flow.

Changes in working capital

You’ll remember from the Income Statement that working capital is the difference between short-term assets and short-term liabilities. Here are the same components of it again:

Accounts receivable and Accounts payable: Accounts receivable is money owed to McDonald’s; over the year, it reduced the amount of cash available to the company by $29 million. Accounts payable on the other hand, is money that McDonald’s owes. Because it hasn’t paid that money yet, it’s sitting on it. In 2012, that amount increased by $124 million.

Inventories, prepaid expenses and other current assets: All those burger patties sitting in some giant freezer; all those vats of ketchup, mustard and relish McDonald’s bought at Costco and keeps stored in its warehouses; all those millions of pre-printed wrappers and drink containers—taken together they are inventory. To a supply manager, they’re backup goods that are needed to make sure McDonald’s restaurants never run out of what they need. To an accountant, they represent cash that is tied up in goods. In 2012, this amount rose by $27 million.

Income taxes: Paying taxes draws money out of the operations of the company. In 2012, that amount rose by $74 million.

Cash Flow from Investing

Companies don’t earn money just from their operations, as important as those are. They also earn money from investments.

But that’s not the same thing as the investments ordinary investors make. Sure, companies can build up a portfolio of stocks and bonds just like everyone else—after all, what’s to stop them? But the investment referred to here is generally of a very different kind. When a company engages in investment activities, it’s usually doing things like building a new factory, buying new equipment, or taking over another company that will help it grow. (Now that last kind of investment does involve buying stocks on the stock market—but on a scale that is very different from the kind the average investor would ever engage in for their portfolio.)

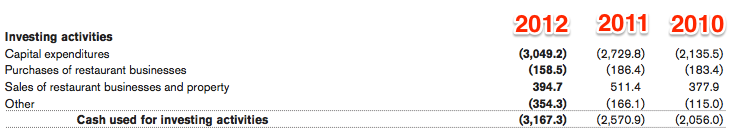

The items on McDonald’s cash flow statement make very clear what is meant by investment activities.

McDonald’s: It’s in the Restaurant Business, Remember?

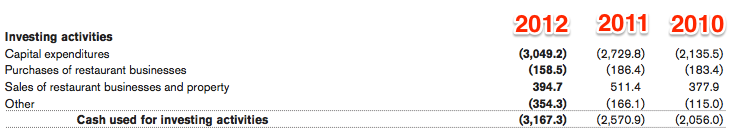

In 2012, McDonald’s had four items in its cash flow statement related to investing. First, there were Capital expenditures. These are easy enough: warehouses, trucks, ovens, fryers, cash registers, gigantic golden arches that it plonks down in front of its restaurants—those all constitute capital expenses. At $3 billion in 2012, that ate up a lot of change.

Then there are Purchases of restaurant businesses and Sales of restaurant businesses and property. These are pretty simple too. McDonald’s is always opening up new locations and closing old ones. Any time it opens a new restaurant, it is going to require money: and the sale will be recorded as a cash outflow. And any time it closes a restaurant and sells the building (if it owns it) and the equipment, it will record the proceeds as a cash inflow. In addition, McDonald’s operates other restaurant brands and has part ownership of other chains; money from buying or selling those will also be recorded here.

In 2012, McDonald’s subtracted $158 million from its cash flow for restaurant purchases, and added $395 million to its cash flow by selling restaurants and equipment.

And then there’s the last item in investing activities: Other. We won’t bother to explain that, because the accountants haven’t bothered to either—all you need to know is whether it’s positive or negative. In 2012, it came to an outflow of $354 million.

Cash Flow From Financing

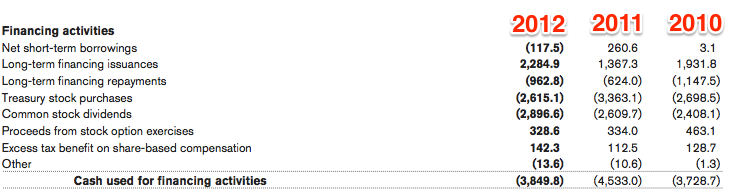

The last element of cash flow is financing activities. This covers anything related to how the company finances its operations—either through debt or issuing stock. There are a lot more things to look at here than in investment activities, but we’ll focus on the really big ones.

Borrowing Money Costs Money…

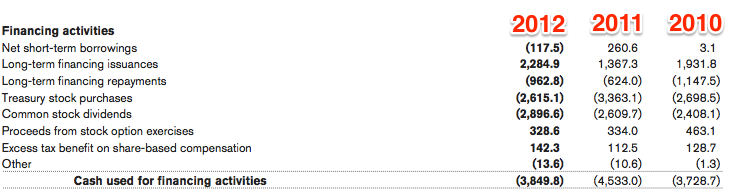

The first item to look out for is Net short-term borrowings. In 2012, McDonald’s saw $117 million drawn from its cash reserves for paying off things like short-term loans from the bank.

Of course it also had long-term borrowings (and this could be anything from long-term loans it arranged with its bank, to long-term corporate bonds it put on the market for investors to buy). Each year, some of those borrowings come due, and they are recorded here as Long-term financing repayments. In 2012, they produced an outflow of $963 million.

The big item in the borrowing category, though, is Long-term financing issuances. At $2.3 billion, it’s a whopper. (Wink, wink.) This is long-term debt that the company has floated on in the market, raising fresh capital. When investors buy all those new McDonald’s corporate bonds, they pour money into the company, so this item is recorded as a cash inflow.

…and Keeping Shareholders Happy Costs Money Too

As you move down the statement, you’ll come to an item that might seem a bit confusing at first. It’s called Treasury stock purchases, and it means that McDonald’s bought back shares on the open market during the year and kept them in its own treasury.

Now why would a company buy its own shares? There can be a number of reasons, but usually it’s done because the company has extra cash on hand and it has decided to make ownership more concentrated. By reducing the number of shares outstanding, it ensures that profits in subsequent years will be distributed across a smaller pool of investors. For any given profit, that will increase earnings per share. And to investors, that’s sweet music. This item shows that in 2012, McDonald’s bought $2.6 billion worth of its own shares.

The next item down on the statement is the biggest one in financing activities: Common stock dividends. Dividends are paid out to shareholders on a regular basis (a little bit like interest is paid out on bonds), and this accounts for a big part of cash outflows. In 2012, McDonald’s gave back $2.9 billion in dividends to its shareholders.

Up until now, we’ve been building your understanding of the cash flow statement categories so we can analyze them next. And guess what, that next part is…well…next.

The Use of Cash

So, we’ve gotten through the big categories that make up cash flow. Let’s look now at how we put them together.

On McDonald’s Cash Flow Statement, there’s an important clue in how these three categories fit with each other. Look at the summary lines of each one. We have Cash provided by operations, and Cash used for investing activities and Cash used for financing activities. What that means is that the first figure ($7.0 billion) is cash that is added to the company by operations; the next two ($3.2 billion and $3.8 billion) are cash that is taken away from the company for investing and financing.

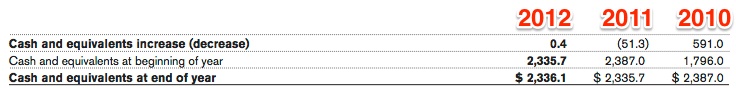

Putting them together, we get: $7.0 – $3.2 – $3.8 = 0. On the statement, this appears on the line here: Cash and equivalents increase (decrease). (The 0.4 comes from rounding the numbers.)

In plain English what this means is simple: McDonald’s was pouring a whole load of cash into its piggy bank during 2012, and took out the same amount by the time the year ended.

OK, but in really plain English what does it mean?

To really get a sense of what is happening to McDonald’s cash flow, let’s look at how it changes over the three years provided, from 2010 to 2012. That can be understood by looking at the cash increase or decrease, and putting it together with the two lines underneath: Cash and equivalents at beginning of year, and Cash and equivalents at end of year.

Now English doesn’t get any plainer than that. In 2010, McDonald’s added $591 million to the cash it held at the beginning of the year ($1.8 billion), so it ended the year with $2.4 billion.

That amount then moved from the end of 2010 to the beginning of 2011. During that year, McDonald’s reduced its pile of cash to the tune of $51 million, so it ended 2011 with $2.3 billion.

And for 2012? You guessed it: it started the year with $2.3 billion, and then added essentially nothing to its cash position—so it ended the year with $2.3 billion as well.

So what this tells you is that one year (2010) McDonald’s had positive cash flow; one year (2011) it had negative cash flow; and one year (2012) it had almost no change in its cash position.

This is a neat example, because it shows you that a healthy company like McDonald’s can cover all three scenarios. While it’s good for a company to have a positive cash flow over the long term, there is nothing inherently bad about a negative one—it depends on why that flow is negative. We’ll turn to that in the final step.

Putting Cash Into Context

From time to time, a company may have a bad quarter, a bad year, or even a bad couple of years. When that happens, cash flow from operations can be negative. But that doesn’t mean you have to give up on the company. Maybe it’s experiencing growing pains, the whole industry sector suffered, or the economy of the entire world was in the doldrums.

But as we said earlier in the course, if cash flow from operations is negative, the company needs to make it positive pretty soon, otherwise it will run into trouble. How long is a bank willing to loan money to a company if the cash it sends out the door consistently exceeds the cash it brings through the door?

Investing Can Change Everything…

The other two kinds of cash flow activities are a bit harder to evaluate, though. Negative cash flows in these areas can be a sign of good things to come, and positive cash flows can actually be an indication that the company is in trouble. Let’s look at investing activities first.

Going back to McDonald’s Cash Flow Statement, you can see that it spent a huge amount of money on capital expenditures. That’s a big negative for cash flow, but obviously is a big positive for the company: it means McDonald’s is modernizing its equipment, renovating its restaurants, developing new products—which will make it even more profitable in the future.

Now consider another item in the investing category: Sales of restaurant businesses and property. In 2012, that was a small, positive addition to cash flow. But what if it was really big—say $3.9 billion, instead of $395 million. That would be hugely positive for cash flow. But would it be positive for McDonald’s?

It could be. But it could also be something negative. For example, let’s say McDonald’s had overexpanded, jamming new restaurants into neighborhoods that were already saturated with fast food outlets; or maybe it had bought a big vegan juice company, only to discover that its products didn’t fit with the McDonald’s menu.

That big cash flow number could be a result of McDonald’s selling those underperforming restaurants, or offloading that vegan juice company after several years of losses. So while it might help McDonald’s manage its overall cash flow, it’s actually telling an important story—McDonald’s is stripping itself of underperforming assets, because it has run into trouble.

…and so Can Financing

Financing activities are also not so straightforward. Take a look again at the second item under Financing activities for McDonald’s: Long-term financing issuances. It’s positive for cash flow, but is it positive for McDonald’s?

Well, that depends. Maybe McDonald’s is issuing long-term corporate bonds at low interest rates (because investors are confident McDonald’s can repay its bondholders). If it’s using that money to develop new products or take over a competitor and earn even bigger profits, that’s good for McDonald’s.

But on the other hand, maybe it’s issuing its own bonds at high interest rates (because investors think that the company is in trouble so they demand a high rate of return on its bonds). Then that number could be a symptom of some underlying problem—people no longer believe in McDonald’s, it’s getting harder for it to raise money, and this bond issue is a case of McDonald’s digging itself into a big hole that will be difficult to get out of down the road.

It Ain’t Easy

Cash Flow is Like Math: It’s Hard

The Cash Flow Statement is probably the hardest financial statement to understand. It’s not a snapshot at a given point, like the Balance Sheet. And it’s not a summary of revenues at the end of the year, like the Income Statement. Instead, it’s a statement of change: how did the cash move in and out of the company over the year.

And in addition to being hard to understand, it’s hard to interpret. If revenues go up or down, it’s pretty easy to say what is happening to the company. That’s not the case with cash flows. A negative cash flow in any given year can mean a lot of different things: the company isn’t earning enough to stay afloat; the company is investing heavily in new markets because it’s poised for growth; or the company is buying back its own shares because it has so much money it doesn’t know what else to do with it.

That’s why it’s important to look at the cash flow statement together with the other statements. They are all telling different parts of the same story. And when you’re investing, you want to know how this story is going to unfold in the next chapters.