A balance sheet is a snapshot of what the company owns and what the company owes. Being able to read and understand a balance sheet is a key component to doing investment research.

What’s a Balance Sheet?

And now for the bad news. From here on in, the material gets really, really dry. No more fun. And no more cake. Just a diet of cold, thick gruel. That’s the way the cookie crumbles, so to speak, except you don’t get the cookie or even the crumbs. That’s how the Victorians did things, and they invented capitalism.

So now that we prepared you for what’s coming, here we go. The Balance Sheet: a big bowl of gruel, and probably the most important piece of information about a company you could ever want.

A Portrait in Numbers

The Balance Sheet is a snapshot of where a company stands at a given point in time. To understand it better, think of it like this: everyone—including you—has a balance sheet.

Sure, you don’t have a balance sheet written down on paper—but you do have a balance sheet. That’s because a balance sheet basically consists of assets and liabilities. And you have both of those things.

To read YOUR balance sheet you would look at: your car, your computer, your bank account, your smart phone, your clothes, that box of Kraft Dinner in your cupboard—those are all things that you own. And because they have value (you could even resell the KD if you wanted to), they are considered assets.

But you can read your balance sheet without looking at your liabilities. Your student loan, your credit card bill, the KD you borrowed from your roommate, even your promise to fill your uncle’s Maserati with gas after he let you borrow it for a joyride—those are all things you owe. And because they have value, they are considered liabilities.

Subtracting your assets from your liabilities will tell you something important about yourself: what your net worth is.

Your mother might not care about that, because she loves you unconditionally—but lots of other people will. If you want to get a loan for a car, take out a mortgage from a bank, or launch a startup with your roommate, your net worth is one thing (among many) that they’ll want to know about. It will give them some idea of what they’re getting into with you.

And the same is true of a company. Its net worth is read on the balance sheet as shareholder equity. This is broken down into two items: shares issued to investors, and earnings it has retained over the years instead of giving back to its shareholders. And a company’s equity is one thing (among many) that potential investors want to know about. It will give them some idea of what they’re getting into with the company.

Taken together these are what form a company’s balance sheet. And you read the balance sheet as a formula: Assets = Liabilities + Shareholder Equity.

Why It’s Important

So, why does knowing how to read the balance sheet matter so much? Very simple. Let’s say you had a ton of liabilities: a massive student loan, three different credit cards with big balances, a debt to your older sister for $2,000, and an obligation to fix up your uncle’s Maserati because you actually CRASHED IT on that joyride. (And as we know, Maseratis don’t come cheap).

And let’s also say that your assets don’t add up to much. Your computer is an old piece of junk worth $100, your smart phone is actually a “smart phone” (that is, all it can do is send texts and make calls), your wardrobe consists of two pairs of jeans and 30 T-shirts, and all you have in your cupboard is that Kraft Dinner that you borrowed—nothing else.

Well, how would you evaluate yourself? Most people would say that you’re going nowhere fast. And if you came to anyone and asked to borrow some money, they’d be crazy to give you even a dime.

Well, the same is true of a company. If when you read a company’s balance sheet, it tells a similar kind of story (lots of liabilities, not much in the way of assets), it’s going to get the same response. It’s not going anywhere, and any investor (or banker) would be crazy to give it one more dime.

That’s why knowing to read the balance sheet is important.

Assets

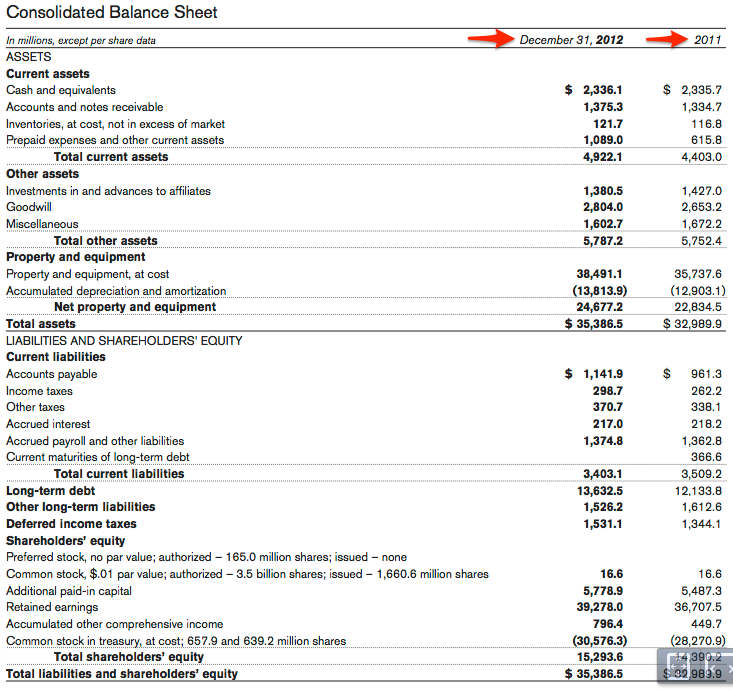

Now, let’s get down to the nitty-gritty. Here’s what an actual balance sheet looks like:

This is the balance sheet for McDonald’s for 2012. And the first thing you’ll notice is the date at the top of the first column on the right: December 31, 2012. What that means is that this is where the company stood on that date. (That’s why it’s called a snapshot, as opposed to a video.) Obviously McDonald’s assets and liabilities will change from day to day and week to week; so it needs to choose a specific date for reporting its financial situation.

Next, you’ll notice the date above the second column on the right: 2011. That’s where the company stood a year earlier. (Even though it doesn’t say “December 31”, it does mean that date.) And it’s put there so you can compare how McDonald’s has changed over the year.

Assets: Who Doesn’t Like ‘em?

As you can see, there are a lot of different items that make up assets. That’s because accountants like to confuse people like you and me. But fortunately, with just a little patience we can understand what they’re doing.

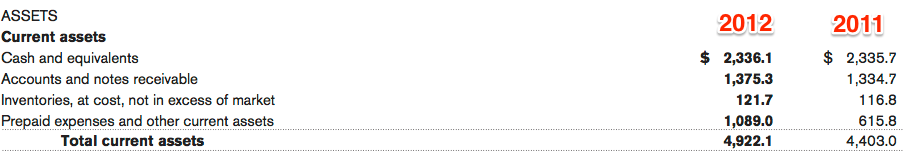

First up, Current Assets. These are anything that will likely be used up within a year, and once you look at the breakdown of Current Assets you’ll see why. It’s made up of:

- Cash (that’s money in McDonald’s bank account);

- Accounts and notes receivable (that’s basically money that is owed to McDonald’s and will be paid soon);

- Inventories (that’s everything McDonald’s has in its warehouses and supply depots—things like those giants vats of “Secret Sauce” that it uses to make its “fresh” Big Macs); and

- Prepaid expenses (stuff that McDonald’s has already paid for and that it can use to make money).

Then there are Other Assets.

Those are not just things that the accountants couldn’t figure out where else to put on the balance sheet. They’re things like the value of patents (like the recipe for that “Secret Sauce”—because McDonald’s could sell that for quite a lot of money), or inventions that haven’t been brought to market yet (like a magic pill that can let you eat endless Big Macs and not gain weight—think how valuable that would be!).

Other assets also include something you might not think of right away: intangibles. These are things like how well known a company is (in McDonald’s case—very). The reason for that is that brand recognition is something that is worth an awful lot, even if you can’t put a specific number on it. To understand that, think of McDonald’s setting up a restaurant in the middle of Beijing. It has instant name recognition, and because of that it has an instant, massive customer base—as well as instant profits.

And finally, there’s the obvious one, Property and equipment. In McDonald’s case it’s a big item, as you can see. And that makes sense: Think of how many McDonald’s restaurants there are all over the world.

And in addition to all those restaurants it owns things like warehouses, trucks, tons of equipment, office buildings, costumes for Ronald McDonald—it takes a lot to run a giant like McDonald’s.

Liabilities

Right underneath Assets on the balance sheet you’ll find the other side of the equation: Liabilities and Shareholders’ Equity.

Liabilities: Who Doesn’t Hate ‘em?

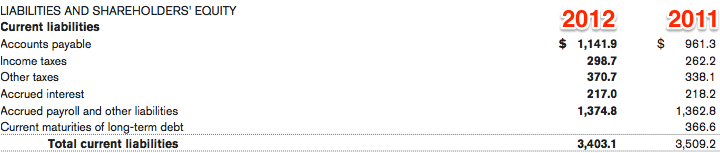

The first component is Current Liabilities. It’s the mirror image of Current Assets because it’s liabilities that are due within a year. There are things like:

- Accounts payable (invoices to McDonald’s for stuff it has already bought—like hamburger patties, frozen fries, new equipment, advertising services)

- Taxes (we all know what those are)

- Payroll that is owing (backdated McWages)

- Maturity of debt (money that McDonald’s has borrowed and that it needs to pay back soon).

Then there are the remaining liabilities:

- Long-term liabilities (that’s basically debt again—except this time it isn’t due for a while)

- Other long-term liabilities

- Deferred income taxes (this is just the accountants playing with your head again—it basically means taxes that are owed but haven’t been paid yet).

So what’s the significance of liabilities? Well, think back to the example about your own personal liabilities. If McDonald’s had a huge amount of liabilities (like a massive amount of debt, or a huge mess of invoices it hasn’t paid yet), it would make you think twice about investing in it. After all, paying off that debt eats into profits. And maybe it wouldn’t even be able to pay off its debt in the long term. A lot of debt can be a black cloud hanging over a company’s future.

Shareholder’s Equity

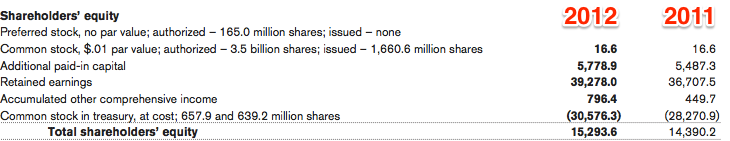

Now we come to the final part of the balance sheet: Shareholder’s Equity. And before we explain what it means, we’re going to point out something important. If you look at where it says Total assets you’ll see that the number there is the same as the one where it says Total liabilities and shareholders’ equity: $35,386.5. (That’s $35 billion dollars, by the way. You didn’t think you could buy McDonald’s for $35K, did you?)

And there’s a good reason for that. First of all, the accountants say so. (Remember in Step 1, Assets = Liabilities + Shareholders’ Equity?)

Second of all, assets have to match up with those other two items. Once again, think back to the example of your “personal balance sheet.” Whatever you own are your assets. Whatever you owe are your liabilities. And the difference between the two is your net worth.

It’s the same for a company. The company’s net worth—what it could get for all its assets once the liabilities are taken care of—is the shareholders’ equity.

Now as you can see from the McDonald’s balance sheet, there are a few different things that go into making up shareholders’ equity.

The big one is Retained earnings, at $39,278.0 ($39 billion). That’s profit McDonald’s earned during 2012 that it didn’t return to its shareholders in the form of dividends. Instead, it held on to this money for future uses, like developing tasty new menu items or remodeling its restaurants to look more high-class.

Then there’s Additional paid-in capital. That’s the accountants having fun again—basically it’s just money the company raised from issuing shares.

And finally, the other big item is Common stock in treasury. That’s $30,576.3 ($31 billion). Stock that is held in treasury comes from shares that McDonald’s issued at one point, and then bought back. It’s shown as negative (that’s what the brackets around the number mean) because when McDonald’s bought those shares, its cash holdings were reduced—which in turn reduced the shareholders’ equity.

(One final note: shareholder equity is not the same thing as common equity, which is a term you’ll come across all the time in investing. Shareholder equity is just something that is found on the balance sheet. Common equity is found in the real world: it’s all the stock that has been issued by the company. When you multiply the common stock outstanding by its price on the stock market, you get the company’s market value (also referred to as the “market cap” or market capitalization).

Leverage

Now to understand a lot of the fine points about the balance sheet, you need an accounting degree. Until you get that degree, let’s forget about the details and focus on the big picture.

One really important part of the big picture is how much the company is leveraged. This is a term you’ll hear a lot in investing. It basically means how much debt the company is carrying, relative to its equity.

How to Grow: Debt or Equity?

McDonald’s can expand its business in two ways. First, it can issue more shares and use the money for whatever it wants: opening new restaurants, developing tasty new menu items, building its presence in growing overseas markets like China. But if it does that, it has to share the increased profits among a larger number of shareholders.

The second way of expanding is to take on debt. This can be a loan from a bank or an issue of corporate bonds—this is called “leveraging” the company.

The advantage of leveraging is that the increased profits aren’t shared among a larger number of shareholders. The drawback is that if McDonald’s expansion plans don’t work out (let’s say that new Tofu Quinoa McMuffin it spent three years developing is a flop), the profits won’t grow—and more of them will now be eaten up by debt payments.

The banks and bondholders, of course, don’t really care. McDonald’s will still be keeping its side of their agreement long after that weird McMuffin has entered the Failed Products Hall of Shame. But what about shareholders? They’re not owed anything, and they’ll just have to accept a lower level of profits – and probably a drop in the share price as well.

Basic Leverage Ratios

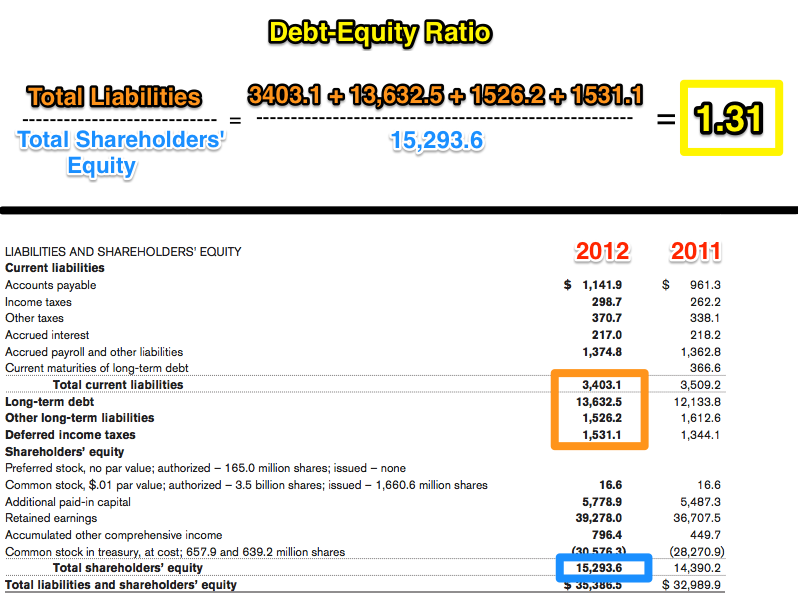

There are a number of ratios that tell you how much leverage a company has, but they all come down to the same thing: comparing liabilities to equity. Probably the most well known is the debt-equity ratio. This is written as follows:

Debt-equity ratio = Total Liabilities/Stockholders’ Equity.

This ratio gives you an idea of how much of the company’s growth is being financed by borrowed money. If the ratio is really low, it means that most of the hard work of growing the company is being done by equity. If the ratio is high, it means that the company had to borrow to drive its expansion.

In McDonald’s case, the ratio looks like this:

So in 2012, McDonald’s debt-equity ratio was 1.31. Is that high? Low? Or just right? Well, that’s a complicated question. The best way to answer it is to:

- Look at the same ratio for McDonald’s competitors

- Look at this ratio for McDonald’s over several years

- Analyze McDonald’s annual report to see what the company might have done to make that ratio go up or down (if it has), and then decide if that is a wise strategy that will pay off

Always remember this: leverage can really “turbocharge” growth, but it involves risk because growth might not materialize as expected.

Getting a Feel for the Company

By now you should be getting a feel for how to make a basic evaluation of a company. That’s because knowing how to read the balance sheet is the key to understanding a company’s financial health.

Think of it like an annual visit to the doctor. At your annual check-up, your doctor looks at the same basic things every time: your weight, your heart rate, your blood pressure, your blood test, your urine test, how you’re sleeping… Those are your body’s fundamentals, and they reveal whether everything is OK or whether there’s some underlying problem that requires deeper investigation.

Similarly, if a company is piling on debt, racking up lots of short-term liabilities or seeing its assets dwindle, that may be a sign that not all is well. The balance sheet will tell you things like that at a glance. And together with the other financial statements it will also tell you the story of where the company has been, and where it’s going.